Why Extricate Worldview - The Weltanschauung?

Checkland (1989) describes Weltanschauung as “the stocks of images in our heads, put there by our origins, upbringing and experience of the world, which we use to make sense of the world and which normally go unquestioned.”

It can elicit some visceral responses: first, it raises red flags if we presume to leave bias unchecked. Second, effective ways to achieve better without taking a knee for ideology exist. So, third, why look back if the only action needed is to flush? It is sufficiently clear that individuals will struggle to find a productive response.

Additionally, what happens when participant-practitioners cannot access an established worldview? Several factors affect accessibility: cultural, societal bias, and financial barriers to the circles eking out that worldview. This is a gravity problem 1 an immovable circumstance for job-seekers and career changers. In contrast, worldviews offer a panacea for others, separating the haves from the have-nots in these situations. It is necessarily true that fit is an issue.

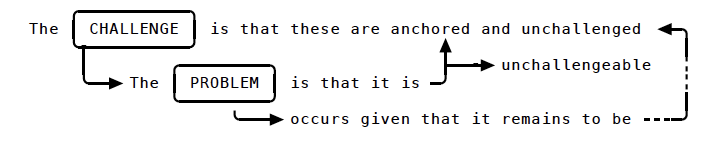

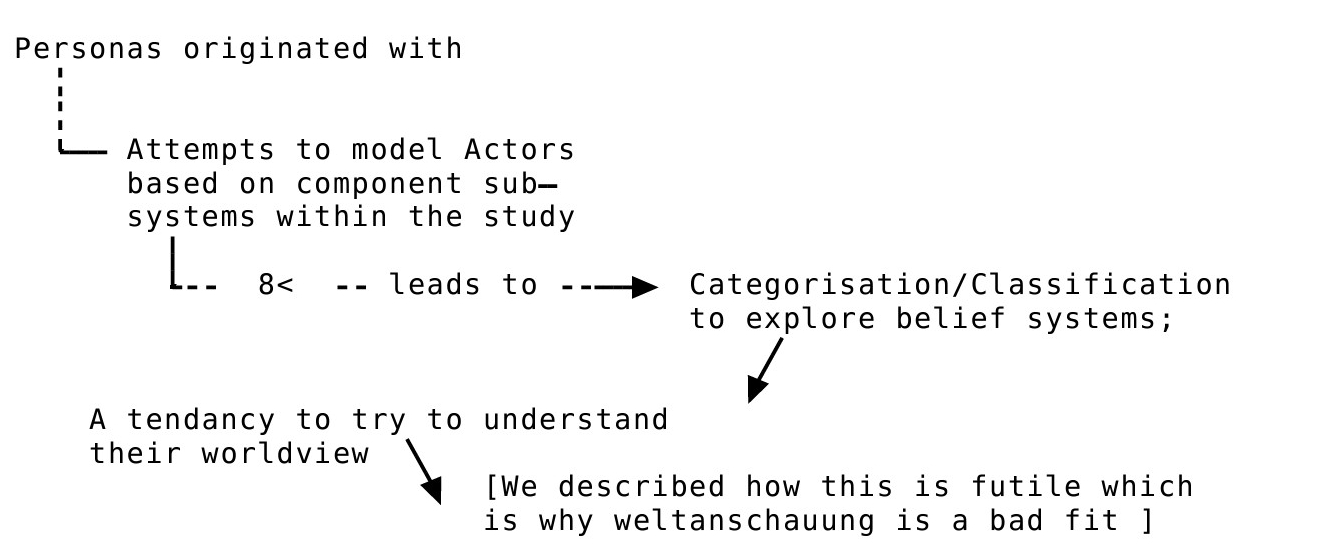

The idea of a universally accepted, communicated worldview raises questions. Yes, these exist and serve well as a bias to action that has proven effective in rallying forces. The challenge remains that worldviews stay anchored and remain unchallenged. (E.g. Figure 1). For the Employment Journey, Finding and Fitting are essential strategies. We have a third strategy in Forming. Where worldviews are invaluable, the Domain of knowledge (D) and domain inheritance are practical viewpoints on finding and fitting, respectively, in place of the Weltanschauung (W).

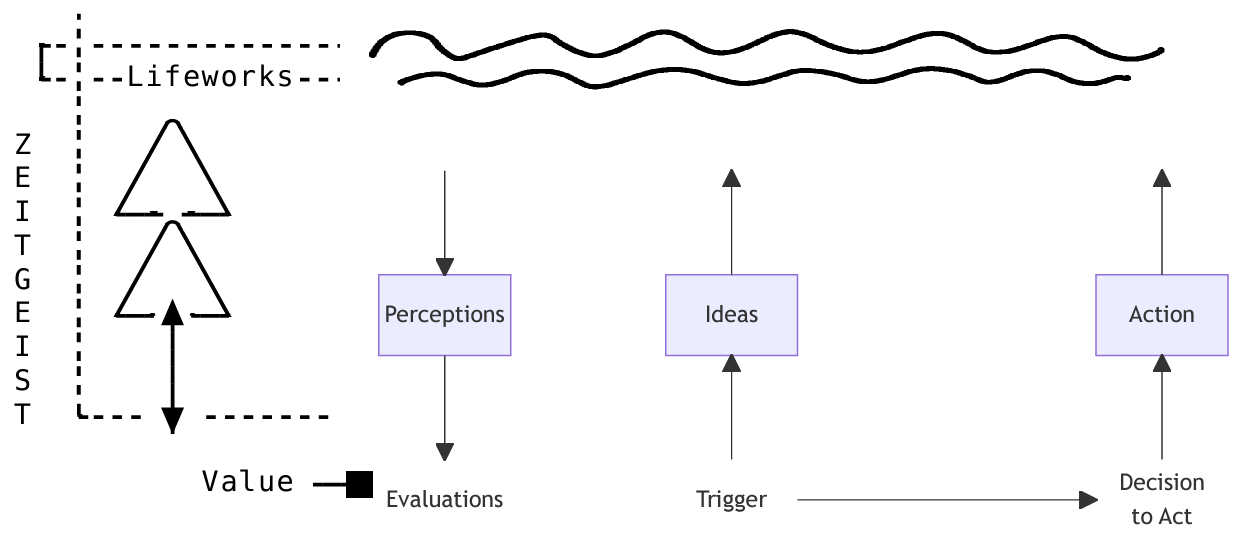

Notably, the third tenet of SSM Checkland (2000) (Checkland, 2001) emphasises the importance of consciously articulating the process to facilitate understanding and improved outcomes. The second tenet of SSM posits that groups and individuals act autonomously, leading to differing evaluations and actions tailored to unique perspectives. We want to leverage diversity and reframe to capitalise on emerging opportunities.

In this context, the concept of ‘zeitgeist’ is particularly relevant. The accompanying figure Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between zeitgeist (Z) and the first tenet of SSM, highlighting how current societal and cultural dynamics can influence system thinking and decision-making processes.

References

Footnotes

(Burnett and Evans, 2016)↩︎