Ideation: The ‘ABCD’ of Design

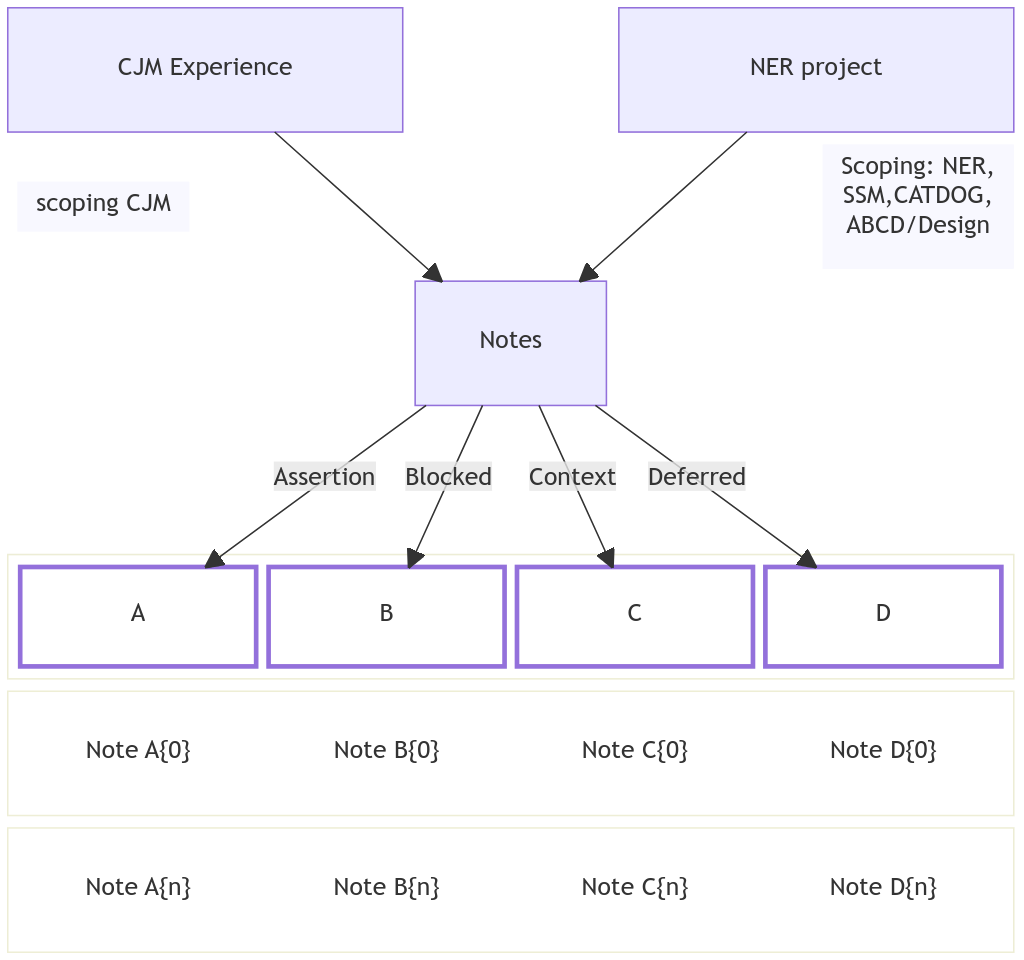

ABCDis an organising heuristic applied as scaffolding to develop themes and ideas of the proposed development at the heart of the study and to enable project tracking against these ideas. It divides design thinking into four areas: Assertions, Blockers, Context (and caveats), and Deferred items. The rationale behind this is that the ABCDapproach materialises design focus on the core components of the study. ABCDcan be replaced wholesale by any other tooling that accomplishes the same. The core idea is that a verifiable process exists to communicate and maintain ideation.

As a simple heuristic, it is akin to the rule of three applied to convey a narrative effectively. Dividing into two helps disseminate a complex idea, giving it shading effectively. Like a quadrant diagram, four parts can help reflect the interrelatedness dimensions. We craft design decisions from understanding these.

Alignment is the initial or central idea within this organising principle for design. Envisage that the study starts at a point of pure enquiry. From a state of Not knowing, a blank slate. Initially, there are effectively two components:

A - Assertions: Represents areas acted upon and core ideas that originated from the exploration exercises, like St.OMP or stemming from goal-setting with Goal Question Metric (GQM) and GROW (Goal, Reality, Options or Obstacles, and Way Forward). Examples of ongoing assertions included “Persona:JOBSEEKER,” “Scaling, Scoping and Goaling As Transformations,” and “Thinking About The Approach.” The proposition is that these are necessary for the project’s success. These assertions reflect a project’s core attributes in play.

B—Blockers: These represent obstacles (or TODO items) instead of deferred tasks D below. These ideas come to a natural rest, to be resumed later when sufficient resources are available and we perceive them differently. This is a design blocker that is separate from engineering parlance.

Blockers arise for different personas, such as \@ENGINEER A Blocker example is NER Searches related to automated article alerts addressed by running manual searches rather than resolving this directly. Engineering can run model categorisation on blocker documentation for report dashboards to help detect problem patterns.

Notably, If AI were used to predict ideas around Assertions, Context, and Deferred content, Blockers would constitute project parameters excluded from these results.

C - Context: Represents areas of activity for focus. In propositional terms, these are sufficient for the success of the elected use case. Every Contextual item C has one or more associated Assertion A. So, we apply reflexive logic for thinking to establish [missed] correlated assertions. Also, it is imperative to implement A, which is critical for the success of C’s implementation. Examples of contextual items categorised as contextual include “Remember the Use Case” and “Journey Advantages.” Context guides a concept, and contextual drift can occur.

For example, Persona:JOBSEEKER becomes \@SEEKER for the project context. While we apply thinking to develop ideas, its origin story can skipped. Having ABCD allows us to track the movement of ideas in terms of timing and context of what else was in the pipeline. ABCD can help identify and scaffold engineering journeys and mapping touchpoints.

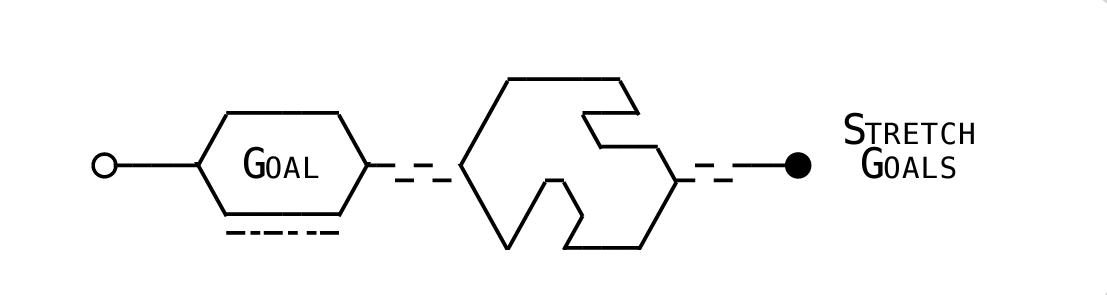

Deferred (D): Refers to items that are set aside, typically as stretch goals or as part of a product roadmap. These may also arise when scoping the deliverables, project direction, and include AI-generated reports needing to be vetted and contextualised. Once the context is established, the deferred item can be marked as completed. Similarly, if stretch goals are achieved, they can provide a foundation for further development.

Goal Setting: Near Reach and Stretch Goals

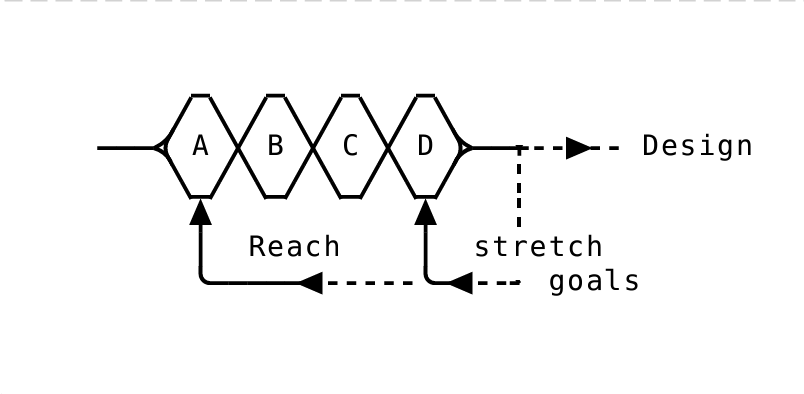

The workflows for ABCD can help address the Stretch Goal Paradox. Sitkin, Miller and See (2017) These are resources for future iteration and deferred until the near-reach goal is identified and attained.

This approach allows @ENGINEERING ABCD to extend it to manage journeys for the @SEEKER as the basis for embedding this into any tooling for goal-setting.

ABCD can help address the Stretch Goal Paradox with a feedback loop ensuring that resources are in place to enforce iterative goal setting, so the practitioner attempts the goal when on the right loop.

This practice pulls on Kanban board, Todo list, Linear notes and sketching.

This iteration adopts Joplin for note-taking. Although Joplin supports freehand sketches, a Kindle tablet device was used for this.